The Power Rap

Late 1993

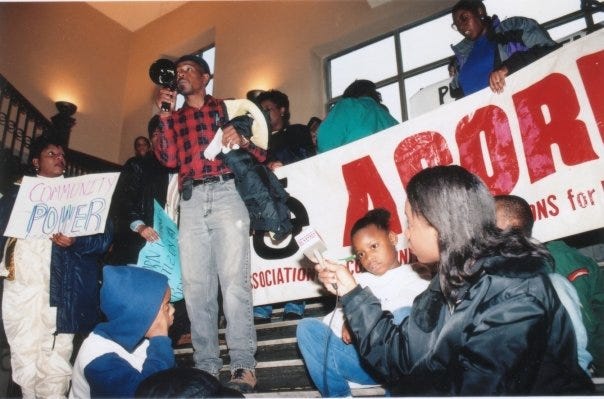

(ACORN members in Little Rock protesting on the steps of city hall while reporter listens in)

When I first walked into the ACORN office in Little Rock, the building itself hit me before anything else. Big brick place near downtown. The kind of building that had been important long before I showed up. It wasn’t shiny. It wasn’t taken care of the way it should have been. Inside, boxes were stacked everywhere. Decades of paper. Old campaigns. Old voter lists. Old signs. It felt less like an office and more like an archive no one had ever closed. Honestly, it was a fire hazard. But it was also alive.

ACORN had started in Arkansas. That mattered. Wade Rathke had been there. Madeline Talbott had been there—tough, disciplined, a great organizer who made a difference in the lives of a lot of Americans. Jon Kest had passed through Hot Springs, where, according to local lore, the dues system was born. Arkansas was where organizers got forged. By the time I arrived, the office had atrophied, but the DNA was still there. You could feel it just standing in the room.

Neil Sealy was there when I came in. Seasoned. Sharp. He knew Arkansas. He was amazing to work with, even though I wasn’t easy to work with—something I understand much better now. Neil stayed after I left and is still organizing he’s a hero to the people of Arkansas.

Jean Conley, Ms. Pleasant, Jason Murphy, and Maggie Dyer were all there with me from the beginning. Jason was younger, had gone to Hendrix, and I was honestly relieved to have someone around my age with real enthusiasm for the job. Maggie was steady and serious. It was an incredible team. Some of the finest organizers I’ve ever known.

And then there was Dixon Bell.

Dixon was an amazing human. He had this deep Arkansas voice and an appetite that matched it. On drives to Pine Bluff, he’d make me stop for pickled pig’s feet and these insane pickled eggs. I’m pretty sure he got banned from at least one buffet. Somehow, despite all that, he stayed incredibly fit because it was so fucking hot in Arkansas and he walked everywhere. But what mattered was the work. Dixon was a servant to real people in Little Rock who wanted to buy homes. He spent years helping families navigate housing systems designed to shut them out, and that work resulted in real change and real wealth being built by people who had never been allowed near it before.

One day Dixon told me that O.J. Simpson was going to get off because he was rich. I didn’t believe him. Then we watched it happen on TV in the office. He was right.

I didn’t invent the power rap in Arkansas. I brought it with me from New York City. That’s where I learned it the hard way. Jon Kest drilled it into me every day—or made someone else do it in front of me—until it was seared into my nervous system. Knock. Introduce yourself like a human. Get inside if you can. Shut up and listen. Ask what actually hurts. Ask what they want changed. Polarize honestly. Then ask them to Join. Then shut the Fuck up in Painful Silence while they decide. Repeat until it works.

ACORN organized poor people. Period. Black, white, Latino—if you were low- or moderate-income, ACORN was your organization. And this wasn’t abstract. People were being actively discriminated against in housing, lending, and employment. Arkansas is segregated as hell, like much of America, and the conditions made the polarization real. Over time, many white members drifted away and the organization became more heavily African American, not by design but because discrimination was hitting some communities harder and more directly. The door stayed open. The work followed the pain.

Before I arrived in Arkansas, ACORN had led campaigns to change municipal elections in multiple jurisdictions using citizen ballot initiatives. Prior to these initiatives, at-large systems were designed to strangle power before it ever reached poor neighborhoods. Using the tools of the Voting Rights Act and ballot initiatives, ACORN helped force ward-based representation in places like Little Rock and Pine Bluff. Pine Bluff was majority Black and had never elected a Black city official until that changed. Power had been engineered away from people. We engineered it back.

The power rap isn’t a script. It’s how you walk into someone’s life without bullshit. You knock on the door. You let them see you’re human. You ask to come inside—which matters more than people realize. When someone lets you into their house, they’re being vulnerable. Honest. That’s when you listen.

People told you everything. Neighborhoods falling apart. Vacant houses. Trash everywhere. Kids stuck in failing schools. Family members in jail. Mortgage scams bleeding them dry. Life was hard—not just in the poorest neighborhoods, but even in places barely holding on. As an organizer, you had to steel yourself to take it all in. The pain. The anger. The skepticism. The rejection. Some people had no money at all and still gave you time. Others couldn’t believe anyone would knock on their door for this reason. Both were real.

The most important question was always the same:

What do you want to see changed?

Then came polarization—not invented, just named.

“Do you think they have vacant houses and trash on the streets in Roland Park?”

People already knew the answer.

You repeat the vision at the end. Over and over. If we get enough people together, we can confront the landlord. We can force the city to act. We can change this. Repetition mattered. People don’t move from hope. They move when something starts to feel possible.

Then you ask them to join. To pay dues. To be part of something. Like a union. On a good day, four signups. That was a win. Over time, people became proud ACORN members—not because it was easy, but because it meant something.

We built more than one organization in Arkansas. A fair housing enforcement group—one of the first in the South. A housing counseling organization. Fair housing work was controversial. It pissed people off. That meant it mattered.

My first major campaign was Gloria Wilson’s city council race. Gloria had been the national president of ACORN. She lived on the East End of Little Rock. No money. No machine. Just people. We knocked on damn near every door. We made homemade signs—real ones—with issues on them: Housing. Jobs. I hated signs that were just names. Politics had to be about something.

We ran caravans. Intersection waves. Neighborhood walks. Community meetings. We counted votes because elections here are winner-take-all. No second place. No consolation prizes. You either win or you have no power at all. Gloria won by ten votes. I’ll never forget her jumping in the air—a straight-up Toyota jump—when the results came in. She was one of the first ACORN members elected to a major office. Many more followed.

ACORN functioned like a family in practice, not in comfort. When an organizer and her two kids needed a place to stay for a week, they stayed with me. Trainees slept on the couch. I was bad at boundaries. That probably made me a good organizer in some ways, and it took me a long time to learn how to live differently. ACORN took a lot from people. What it gave back wasn’t care or balance—it was progress. What sustained you was building something real and watching it work.

ACORN was smart about infrastructure, too. Radio mattered. I met my wife at a training in Chicago. She later moved to Little Rock to run the station. She’s an amazing human, like the most amazing human.

Behind the phone was Zach Polett, doing the job I was supposed to be doing while also being a national force. Zach has passed. We disagreed deeply. He was loyal to ACORN in ways I never fully was. I’m loyal to my own values about what’s right in the world, even when that creates friction. I learned that from my family—the Klein family's belief that America matters, not as mythology, but as responsibility. Making it better for every American. That belief came out of a lot of pain. And that pain has been something that I’ve been dealing with in my head my whole life.

My father believed that as a scientist working for America, he was helping prevent the next big war. For a time, maybe he was right. But war scaled anyway—farther away, more mechanized, more profitable, more brutal.

Throughout my life I’ve kept taking on impossible projects. Different domains. Same method. The power rap never left me. Neither did what I think of as the Klein learning-to-learn algorithm—shaped by my OCD and related wiring, not despite them. Pattern recognition. Repetition. Relentless refinement. Those traits let me build things from nothing. From an idea. The same way organizing works.

Organizing is taking pain and turning it into action. People being empowered to do something about their own lives. Through collective action, we change the world. That belief carried into everything I built afterward.

Today, AI is changing how influence works. Messaging is centralized. Psychographic targeting is real. A few people decide what gets amplified and what gets buried. That’s not new—it’s just faster now. Organizing still matters because it’s human. And if AI is going to mean anything good, it must make collective action easier, cheaper, and more accessible to people who have never had power. It actually has to be the answer to human suffering.

The future still belongs to people working together in small groups.

Always has.

That’s the power rap.

Brillaint piece on what organizing actually looked like before everything got digitized. The part about Gloria's 10-vote margin really captures how those repetitive door knocks build sometihng real that polls and data models just cant replicate. I ran a small voter outreach thing back in college and found people care way less about slick messaging than just being treated like their problems matter. Wonder if AI will acutally lower the barrier or just become another tool for existing power structures.